“Is this really happening?”

Get used to those four words, people. You’ll be asking yourself that a lot during Words and Pictures, a big letdown that wavers between an overplayed drama, an awkward romantic comedy, and hokey classroom schmaltz.

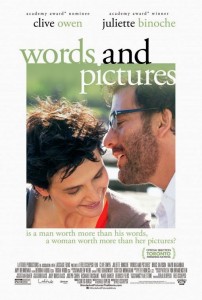

Despite that harsh statement, Words and Pictures isn’t flat-out bad. We at least have watchable performances by Clive Owen and Juliette Binoche. Their roles as teachers who butt heads (Binoche being the more artistically pragmatic type, Owen as the frisky class clown) are stereotyped, but they don’t necessarily do a poor job at carrying out what director Fred Schepisi wants them to do. If Owen has to portray one of the character’s countless drunken stupors, he does so quite well. If Binoche has to sombrely remind the audience of her handicapped functions and how “art is life”, she dives into the stifling material.

However, Gerald Di Pego’s screenplay asks his characters to do a lot of the same. Their flaws are excessively presented to a point where the audience is tired of seeing two capable actors – of whom we hardly see on-screen nowadays – ineffectually utilized.

But because both the snarky wordsmith and the pouty painter are eccentric personalities, they’re made for each other and develop a love/hate relationship that’s heavier on “hate” from Binoche’s point-of-view.

Their differences and standoffish attitudes lead to a competition where the debate between the importance of words and pictures will take place by the end of Schepisi’s movie. This means the audience receives too many scenes of two otherwise talented actors arguing like children about two areas movie goers couldn’t care less about.

I’m inclined to say this off-putting effect was intentional since their oddball relationship runs parallel with a younger yet similar situation (a cocky teenage male relentlessly teases a quiet sketch artist), but this doesn’t work as well as Di Pego may have had in mind.

In fact, a lot of Di Pego’s dialogue has the presence of sounding “ok” on paper and not making a smooth sail to the screen. Clive Owen’s merciless Jack Marcus insists on using the artist’s last name as a playful gesture to get her attention. This sounds like a normal way for another character to address someone else, but Di Pego writes Jack to insistently work in the name “Delsanto” as often as possible over the film’s gratuitous runtime.

The chemistry inside the school reeks of contrived co-operation and false amiability, and the students all appear stiff in front of the camera. Instead of having the audience inspired along with the class, we’re left cringing – such as the scene where the kids are thinking of new words.

But, this film is non-stop with how frequent words and pictures are brought up. I know the title says it all, but a screenwriter and director need to know when the usage is starting to sink the movie. Are we really listening to people bicker this? Are people in the movie really that enthused about any of this? Are these people really falling for each other? Is this really happening?

Be the first to comment