It’s hard to watch The Other Woman without bringing into the equation James Toback’s remarkable 1997 feature Two Girls and a Guy, a talk-heavy, one-room dramedy about two women (played by Heather Graham and Natasha Gregson Wagner) who discover they are dating the same man (played by Robert Downey, Jr.) and then conspire to make him suffer for his cheating ways. The movie found ingenuity in the shameless rationale of its male character and the strange alliance-rivalry between the two female leads.

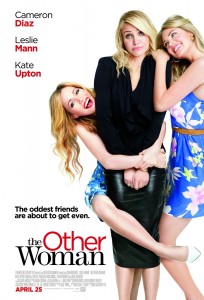

Seventeen years later, Nick Cassavetes (The Notebook) brings us a Hollywood-borne version of this revenge tale, starring Cameron Diaz and Leslie Mann as the “two girls” and Games of Thrones’s Nikolaj Coster-Waldau as the “guy”. This plain-vanilla update, The Other Woman, lacks the cerebral, stripped-down nature of Toback’s version and instead, with a bigger budget and thus more sights to see, privileges broad jokes, a bigger scope, and conventions more conducive to the expectations of mainstream moviegoers.

And for what it is, The Other Woman kind of works. It benefits from a soft, somewhat politically incorrect mean streak of the funnies that derive from the cynical disposition that monogamy, ultimately, is a sham. The comedy is motivated from situations where love and marriage prove to be a recipe for bitter feelings, broken hearts, and betrayals. But since the film’s catharsis comes from exacting sweet, sweet revenge on a chauvinistic pig, Cassavetes must believe – somewhere within this film’s display of scatalogical jokes and wild pratfalls – that polygamy comes with a heavy, ungrateful price.

Like Two Girls and a Guy, The Other Woman shows how, even in their anger and thirst for revenge, the two women kind of get pulled back into the player’s orbit and almost convince themselves he is really a good guy. As the opening sequence demonstrates, the libertine in question, Mark King, is dashing and full of charisma. Cassavetes uses slow and sensual camera movements to show how Carly (Diaz) succumbs to Mark’s deceitful spell of suaveness over a ritzy wine-and-dine date.

Soon after at one of her surprise trysts with Mark at his home in Connecticut, Carly bumps into Kate (Mann) and the awful truth is spilt. Their reactions play into the two comediennes’s acting personas: Carly is a posh business woman and hardheaded individualist, basically a less devious embodiment of her villainess in Ridley Scott’s The Counselor, who immediately opts for cold revenge; whereas Kate is a sobbing, frizzled neurotic with deep anxieties about middle age and the single life, recalling her antsy character from Judd Apatow’s underrated This is 40.

Cassavetes looks for comedy mostly in Mann’s character. Her exaggerated distress is a target for quick-and-easy laughs, such as when Kate acts out in Carly’s high-rise office, and asks in a fit of desperation if the glass windows open. She also has a pet Dalmatian that’s about half her height and only purpose is to leave excrements on Carly’s fancy condominium floor. Meanwhile, Carly is straight counterpoint to Kate’s constant distress, and channels her new friend’s manic behaviour in the direction toward vengeance.

This scheme leads to a series of comedic set pieces that don’t pay off nearly as well as they could or should. One involves Carly and Kate tailing Mark to the Mission: Impossible soundtrack. The whole premise comes off kind of lame and try-hard. A slightly better sight gag shows Carly staggering with pigeon toes along the beach after Mark’s third flame Amber (Kate Upton), a younger belle who runs across the shore in a hypnotic, Pamela Anderson-inspired sway. The scene lands some laughs in spite of itself.

The core of this comedy film ends up being the temperamental relationship between Carly and Kate. Amber just sort of stands there and walks with the occasional sexy strut as the other women devise a plan that will make Mark wish he never had such an uncontrollable libido. You also have singer Nicki Minaj as Carly’s secretary, who passes on advice like “selfish people live longer” her superior’s way. Minaj is one of those actresses who is more a series of postures than a singular presence.

For what The Other Woman sets out to do, I suppose it achieves. It’s a very minor divertissement by Cassavetes, who’s made better films like Alpha Dog and My Sister’s Keeper. Still, this director has a weird way of taking on tacky material and hitting odd notes of sincerity. Undeniably, Diaz and Mann’s work here extends beyond the grasp of Melissa Stack’s screenplay. The Other Woman is not a movie that will be remembered, but it ought to rile up a few biting laughs from folks who see love as much a game as it is an emotion.

Be the first to comment