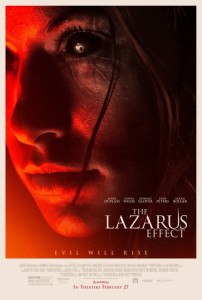

David Gelb’s The Lazarus Effect offers an intriguing concept, but gets bogged down by convention.

Despite its compelling concept, the premise is familiar: a group of researchers led by Frank (Mark Duplass) and his fiancée Zoe (Olivia Wilde) create the “Lazarus” serum, a formula that brings the recently deceased back to life. This God-like power to cheat death causes things to go awry very quickly. Zoe is killed in a laboratory accident and brought back to life with the serum. However, she returns from the afterlife with uncontrollable psychic powers that, unsurprisingly, place the entire crew in grave danger.

The film heavily borrows ideas and scenes from recognizable sources. The Lazarus Effect is essentially the horror version of last summer’s Lucy, complete with illogical supernatural powers caused by increasingly erratic brain activity (screenwriters Luke Dawson and Jeremy Slater even rehash the same urban myth used in Lucy that we only use 10% of our brain). Other citations are verbally pointed out by the characters: these include Stephen King’s rabid dog story Cujo (much of the first act is concerned with a resurrected dog) and Mary Shelley’s seminal gothic horror novel Frankenstein. But clearly they’ve never seen Jurassic Park.

At its moral centre, the film is concerned with the ethics of playing God by scientifically revitalizing the dead. Underlying this is a vaguely cautionary take on euthanasia. Intellectual considerations of the horror genre argue that the monster–in this case the resurrected psychic/psychopathic Zoe–is frightening because it represents a social fear or anxiety (the anti-communist subtext of Invasion of the Body Snatchers is a good example). Zoe’s resurrection by scientific means defies both nature and religion (her body even rejects the basic essences of life, such as a water, in a key scene). Her hellish abilities punish the rest of the cast for their secular curiosity: death, in other words, is the ultimate penalty for playing God and disrupting nature’s balance.

Regardless of where you stand on the euthanasia debate, as a horror film, The Lazarus Effect fails to frighten. Genre thrives not necessarily on what it invents, but on what it innovates. Although it is shot mostly in third person perspective, the camera of student filmmaker Eva (Sarah Bolger)–who is assigned to film the crew’s findings and experiments–provides the film with some of the popular found footage realism of Paranormal Activity and Cloverfield, although it is never used successfully. Some recent horror films, such as James Wan’s The Conjuring and Insidious: Chapter Two intricately mixed third and first person, relying on each perspective’s strengths to terrify audiences. Here, the use of realism is incredibly cynical. It is never able to fulfill realism’s promise of generating authentic scares. It’s only function, it seems, is to jump on the ever-popular found footage bandwagon.

The rest of the film relies heavily on convention. The scares themselves are few and far in-between (a death sentence, really, for an 80 minute film), all of which are ineffective, predictable timed jumps scares. Some of this might be explained by director David Gelb’s lack of versatility. His last feature–2011’s Jiro Dreams of Sushi–was a charming documentary about sushi. Gelb is unable to transition smoothly from documentary to genre filmmaking, suggesting that he should clearly stick to docs.

Blandly executed, The Lazarus Effect ironically lacks a pulse. You’re better off watching Flatliners.

Leave a comment