By: Jessica Goddard

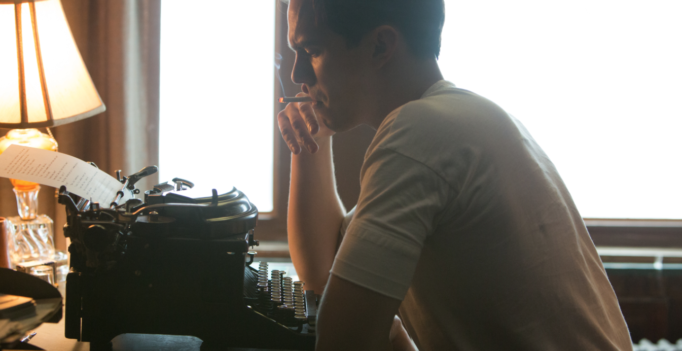

The writing instructor continuously trying to put down his most gifted student in hopes of making him better and stronger. A father who doesn’t want to indulge his son’s delusions of a career as a professional writer. The sight of a Capital A “artist” bent over his typewriter in an otherwise empty, white room. These are just a few of the many contrivances the viewer of Rebel in the Rye is subjected to in their innocent pursuit of the biography of The Catcher in the Rye’s author.

A young J.D. Salinger (Nicholas Hoult) grows up privileged in New York, chasing girls, attending writing classes at Columbia, trying to make a name for himself in the insular New York literary scene. World War II throws a pretty solid wrench in his progress developing his famous novel, as he returns home an unrecognizable man with PTSD and severe writer’s block. This biopic most thoroughly explores Salinger’s relationship with Whit Burnett, his creative writing instructor and mentor, until, well, it doesn’t.

This film gives us too much of what we don’t need to see, and too little of what we do. We don’t get a lot of insight into why The Catcher in the Rye came to be, just how (the film makes it seem like the only reason the now-classic American novel exists is because Kevin Spacey’s Burnett kept bugging Salinger to write it until Salinger finally relented and put pen to paper). Once Salinger’s career begins gaining momentum, we’re told by everyone that his work is brilliant, and once The Catcher in the Rye hits shelves, we’re told it defines a generation, but we never get to know in any intimate way how anyone is affected by its story. This film tells you constantly “he’s a genius”, without bothering to really show you.

Then there’s the absolutely hideous title. Not only does it weirdly demonstrate a misunderstanding of the subject matter it’s supposed to be serving, but characterizing J.D. Salinger as a “rebel” is a little cringeworthy and on-the-nose for a movie that manages to make a fascinating person look like a pretentious stereotype.

A strength of the film is how it ambiguously portrays Salinger’s later life, perhaps the period he’s best known for. We see Salinger hostilely cut off contact from most of the people who helped him get where he is, neglect his young family, and close off his life to anything other than meditation and writing pieces that he refuses to allow anyone to publish. It’s commendably unclear whether the film means to praise this eccentric hero or gingerly lament the unnecessary waste of this unique talent.

Ultimately, writer/director Danny Strong’s screenplay doesn’t care that we’ve watched a bright, interesting, sensitive talent transform into a cold, unforgiving, cynical narcissist who resents the success he’s looked forward to his whole life. It’s unfortunate, and a shame for a concept that had potential.

Then again, maybe I’m just one of the “phony” few who are too engulfed in my comfortable mainstream society to understand.

**********

Do You Tweet? Follow These Tweeple:

Jessica Goddard: @TheJGod

Be the first to comment